The San Jose location of WWDC, Apple’s annual developer conference, felt a bit odd, but Apple sought to strike a familiar tone: the artwork on and around the San Jose McEnery Convention Center featured a top-down view of humans, and a familiar message:

The idea of Apple existing at the intersection of technology and liberal arts was central to the late Steve Jobs’ conception of Apple and, without question, a critical factor when it came to Apple’s success: at a time when technology was becoming accessible to consumers and their daily lives Apple created products — one product, really, the iPhone — that appealed to consumers not only because of what it did but how it did it.

That said, it was telling that this artwork and the sentiment it signified were not referenced in the keynote itself; after a humorous skit about a world without apps, Tim Cook delivered platitudes about how Apple and its developers were on a “collective mission to change the world”, and immediately launched into what he said were six important announcements. It was not dissimilar to Sundar Pichai’s opening at Google I/O: when the announcements that matter are grounded on the realities of a company’s core competencies and position in the market, vision can feel extraneous.

Apple’s Announcements

Cook’s first four announcements spoke to those core capabilities and the position they afford Apple (or don’t, as the case may be) in the markets in which it competes:

tvOS: It was generous of Cook to give tvOS top billing: the only announcement of note was the upcoming availability of Amazon Prime Video on Apple TV. That itself is a reminder of Apple’s diminished position in the space: winning in TV is not about hardware or software, much less the integration of the two, but rather content. The brevity of this announcement — there wasn’t even the traditional executive hand-off — spoke to Apple’s status as an also-ran.

watchOS: This garnered more time, and the headline feature was the Siri watch face. The watch face, which implied a broadening of Siri’s brand from voice to context-based general assistant, seeks to anticipate and deliver the information you need when you need it. The model is Google Now; the difference is that Siri is now housed in an attractive and increasingly popular watch that works natively with an iPhone, while the equivalent Google service requires not simply a different watch but a different phone entirely. It is a testament to Apple’s biggest advantage: thanks to the iPhone the company already owns the “best” customers,1 frequently rendering moot Google’s superiority in managing information.

A computer vulnerability is a cybersecurity term that refers to a defect in a system that can leave it open to attack. This vulnerability could also refer to any type of weakness present in a computer itself, in a set of procedures, or in anything that allows information security to be exposed to a threat. The 'classic' Mac OS is the original Macintosh operating system that was introduced in 1984 alongside the first Macintosh and remained in primary use on Macs until the introduction of Mac OS X in 2001. Apple released the original Macintosh on January 24, 1984; its early system software was partially based on the Lisa OS and the Xerox PARC Alto computer, which former Apple CEO Steve Jobs.

Weakness Mac Os Sierra

macOS: This actually encompassed two of Cook’s six promised announcements;2 the separation of MacOS and Mac computers was, I suspect, born of Apple’s desire to convince developers and other pro users that the company was not abandoning their favorite platform. Moreover, the addition of hardware announcements, after several years in which WWDC was software only, resulted in a very different feel to this keynote: after all, hardware is exciting, even if, in the long run, it is software that actually matters. That feeling, though, goes to the very core of what Apple sells: superior hardware differentiated — and thus sold at a handsome margin — by exclusive software.

As is always the case with the modern incarnation of Apple, though, the announcements that truly mattered centered around iOS.

iOS 11

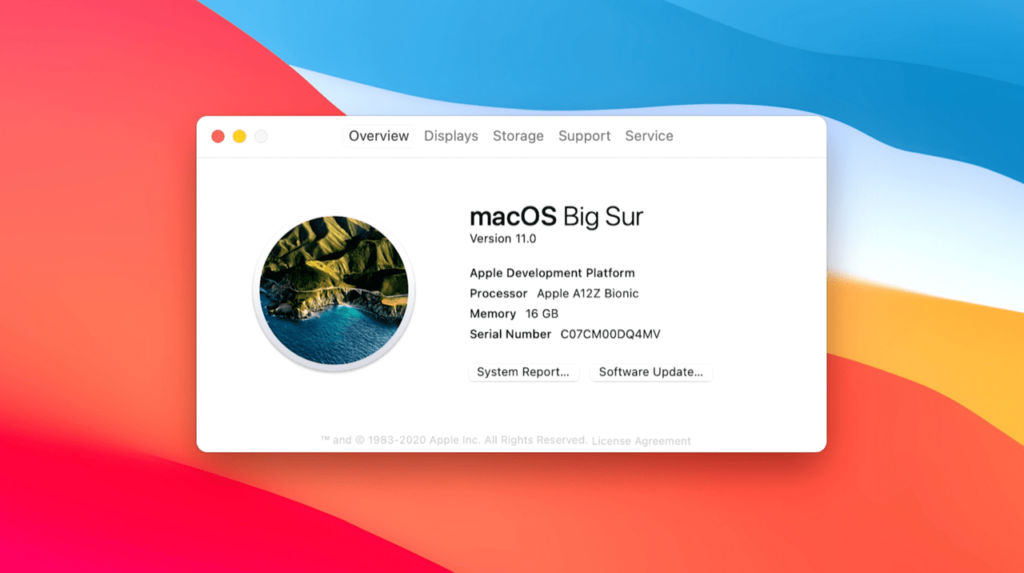

For a MP 5,1 the easiest way is to upgrade to the current Mac OS version which is Big Sur. Keep in mind that there is a lot more to IT security than an updated OS (the most important factor in any security chain is the user), but it means your MP 5,1 is roughly at a same security level as a newer Mac. Weakness in Zoom for macOS allows local attackers to hijack camera and microphone Zoom's use of insecure system APIs allow attackers to elevate privileges as well.

The iOS-related announcements, despite being only one of Cook’s “Big Six”, could have been their own keynote; given the importance of mobile generally and iOS specifically that would have been more than justified. Taken as a whole the iOS segment in particular highlighted what Apple does best, what it struggles with, and what reasons there are to be both optimistic and pessimistic about the company’s fortunes in the long run.

Strength: Defaults

Controlling one of the two dominant mobile operating systems grants Apple the power of defaults. That means iMessage is both an iPhone lock-in and a channel to introduce new services like person-to-person Apple Pay. Siri can be accessed both via voice and the home button, and, just similar to the WatchOS update, is increasingly integrated throughout the operating system. Photos and Maps are used by the majority of iPhone customers, even if alternatives offer superior functionality.

Weakness: Limited Reach

At the same time, iMessage will never reach the dominance of a service like WeChat because it is limited to Apple’s own platforms — as it should be! iMessage is the canonical example of how strengths and weaknesses are two sides of the same coin: it is iMessage’s exclusivity that allows it to be a lock-in, and it is that same exclusivity that limits the standalone value.

Strength: Hardware Integration

Peppered throughout Apple’s presentation were seemingly small features like new compression algorithms that depend on Apple controlling everything from Messages to the camera to the processor that makes it all work. The most impressive example was ARKit: in one fell swoop Apple leaped ahead of the rest of the industry in the race to realize the promise of augmented reality. The contrast to Facebook was striking: while the social network is seeking to leverage its control of content distribution to lure developers to build on Facebook’s “camera”, Apple is not only offering the same opportunity (the results of which can, of course, be shared on Facebook or Instagram), but also delivering a superior set of APIs that, by virtue of being part of that vertical stack, are both more powerful and accessible than anything a 3rd-party application can deliver.

Weakness: Services

While Apple bragged about Siri’s natural language capabilities and alluded to a limited number of new “intents” that can be leveraged by apps, it is not an accident that there were no slides about accuracy, speed, or developer support: Siri is well behind the competition in all three. More fundamentally, all of Apple’s services are intrinsically limited by the fact that they exist to sell Apple hardware: those services, and the teams that work on them, will never be the most important people in the company, and their development will be constrained by the culture of Apple itself.

Strength: Privacy

Apple not only touted its privacy credentials, it also showed off new features to actively limit things like autoplaying videos and advertising networks that follow you across sites. As a user both are very welcome; strategically, both features follow from the fact that Apple makes money on its hardware, while companies like Google, Facebook, and other online businesses rely on advertising and the collection of data.

Weakness: Data

Collecting data is useful for more than advertising, though. Here Google is the obvious counter: certainly the search company wants to better target advertisements, but the benefits gained from data go far beyond overt monetization. It is data that drives Google’s superior machine learning capabilities and the customer-friendly features that follow in apps like Google Photos. Interestingly, Apple made moves in this direction, syncing things like facial recognition data and Messages across devices, favoring convenience over a very slight increase in the risk to privacy. To be clear, the data will still be encrypted, both in transit and at rest, but that is my point: encryption means that Apple cannot leverage the data it will now store to make its services better.

Strength: The App Store

The strategic role of 3rd-party apps has shifted over time: once a differentiator for iOS, Android has largely reached parity, and apps are now table stakes. They are also a big moneymaker: Apple has been pushing the narrative on Wall Street that it is a services company, fueled by the $30 billion the company has collected from app sales and especially in-app purchases in free-to-play games; 30% of that total has come in the last year alone. Make no mistake, this is a compelling narrative: iPhone growth may be slowing in the face of saturation and elongated update cycles, but that only means there is that large of a base from which to earn App Store revenue.

Weakness: Developer Economics

The success of free-to-play games and the associated in-app purchases has come at a cost, specifically, management blindness to the fact that the rest of the developer ecosystem isn’t nearly as healthy, and that the App Store is no longer a differentiator from Android. The fundamental problem remains that for productivity apps in particular it is necessary to monetize your best customers over time; Apple has improved the situation, particularly with the addition of subscription pricing and de facto trials (basically, starting a subscription at $0), but hasn’t made any moves to support trials or upgrade pricing for paid apps, despite the fact that is the proven successful model for productivity applications on the Mac. I have long argued that bad developer economics is the fundamental reason that the iPad hasn’t fulfilled its potential; yesterday’s iPad software enhancements were welcome and will help, but I suspect letting developers set their own business models would be even more transformative.

Weakness Microsoft

Strength and Weakness: Business Model

This point is part and parcel with all of the above: Apple’s strengths derive from the fact it sells software-differentiated hardware for a significant margin, which allows for exclusive apps and services set as defaults, deep integration from chipset to API, a focus on privacy, and total control of the developer ecosystem. And, on the flipside, Apple only reaches a segment of the market, is less incentivized and capable of delivering superior services, has less data, and can afford to take developers for granted.

HomePod

Apple’s final announcement encapsulated all of these tensions. The long-rumored competitor to Amazon Echo and Google Home was, fascinatingly, framed as anything but. Cook began the unveiling by referencing Apple’s longtime focus on music, and indeed, the first several minutes of the HomePod introduction were entirely about its quality as a speaker. It was, in my estimation, an incredibly smart approach: if you are losing the game, as Siri is to Alexa and Google, best to change the rules, and having heard the HomePod, its sound quality is significantly better than the Amazon Echo (and, one can safely assume, Google Home). Moreover, the ability to link multiple HomePods together is bad news for Sonos in particular (the HomePod sounded significantly better than the Sonos Play 3 as well).

Of course, superior sound quality is what you would expect from a significantly more expensive speaker: the HomePod costs $350, while the Sonos Play 3 is $300, and the Amazon Echo is $150. From Apple’s perspective, though, a high price is a feature, not a bug: remember, the company has a hardware-based business model, which means there needs to be room for a meaningful margin. The Echo is the opposite: because it is a hardware means to the service ends that is Amazon, it can be priced with much lower margins and, as has already happened, be augmented with even cheaper devices like Echo Dots (or, in the case of the Echo Show, offer more functionality for a price that is still more than $100 cheaper than the HomePod).

The result is a product that, beyond being massively late to market (in part because of iPhone-induced myopia), is inferior to the competition on two of three possible vectors: the HomePod is significantly more expensive than an Echo or Google Home, it has an inferior voice assistant, but it has a better speaker. That is not as bad as it sounds: after all, the iPhone is significantly more expensive than most other smartphones, it has inferior built-in services, but it has a superior user experience otherwise. The difference — and this is why the iPhone is so much more dominant than any other Apple product — is that everyone already needs a phone; the only question is which one. It remains to be seen how many people need a truly impressive speaker.

This, broadly speaking, is the challenge for Apple moving forward: in what other categories does its business model (and everything that is tied up into that, including the company’s product development process, culture, etc.) create an advantage instead of a disadvantage? What existing needs can be met with a superior user experience, or what new needs — like the previously unknown need for wireless headphones that are always charged — can be created? To be clear, the iPhone is and will continue to be a juggernaut for a long time to come; indeed, it is so dominant that Apple could not change the underlying business model and resultant strengths and weaknesses even if they tried.

- Speaking strictly of which customers generate the most monetary value either through their purchases or advertising targeting [↩]

- iPad hardware and optimizations all fell under the iOS umbrella [↩]